We carry out Daylight and Sunlight Assessments of proposed development schemes, to prepare reports to provide to Local Authorities, day in, day out. However, we sometimes come across simple oversights in design that can have a significant bearing upon whether the proposed new accommodation will be capable of receiving good levels of daylight and sunlight. Local Authority planning departments need to know that newly designed residential accommodation will accommodate the requirements of future occupiers, and hence why they need to understand that such accommodation will have adequate levels of natural lighting.

For a scheme to stand the best chances of passing the daylight and sunlight criteria that is laid down in the Building Research Establishment Guide “Site Layout Planning for Daylight and Sunlight – A Guide to Good Practice, 3rd Edition” (often known as BR209, BRE209 or the BRE Guide), the design needs to be such that the requirements of the Guide are considered at an early stage.

All too often we get asked to assess schemes that fail to consider fundamental design considerations, resulting in assessments that do not meet the BRE criteria. Such reports will not help the planning application; indeed, they will prove to the Local Authority that sufficient thought has not be given to good design for natural lighting. The result of this is often re-design, and of course, re-assessment of the daylight and sunlight outputs of this reconfigured scheme. This causes delays and additional costs to the applicant.

It is far better to try to optimise the design from the outset.

Below are considerations outlined in the BRE Guide that should be used as a guide by designers:

Daylight Considerations

Sky View

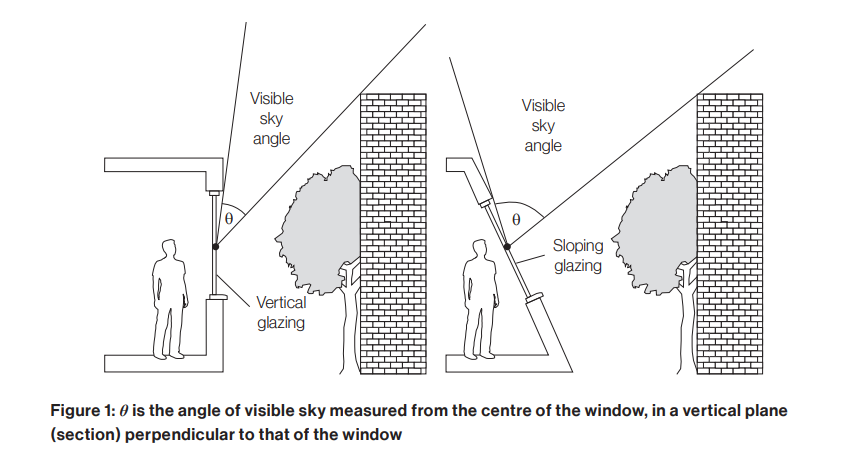

The BRE Guide requires domestic rooms to have certain minimum levels of daylight. This is naturally helped by giving dwellings good-sized window openings to afford the rooms within as good a view of the sky as possible. The BRE Guide has a diagram (Figure 1) which illustrates this principal:

The Guide states in section 2.1.6:

“The amount of daylight a room needs depends on what it is being used for. But roughly speaking, if θ is:

– greater than 65° (obstruction angle less than 25° or VSC at least 27%) conventional window design will usually give reasonable results.

– between 45° and 65° (obstruction angle between 25° and 45°, VSC between 15% and 27%) special measures (larger windows, changes to room layout) are usually needed to provide adequate daylight.

– between 25° and 45° (obstruction angle between 45° and 65°, VSC between 5% and 15%) it is very difficult to provide adequate daylight unless very large windows are used.

– less than 25° (obstruction angle greater than 65°, VSC less than 5%) it is often impossible to achieve reasonable daylight, even if the whole window wall is glazed”.

Therefore, try to ensure θ angle is as large as possible to give best clear view of sky having regards to obstructing buildings.

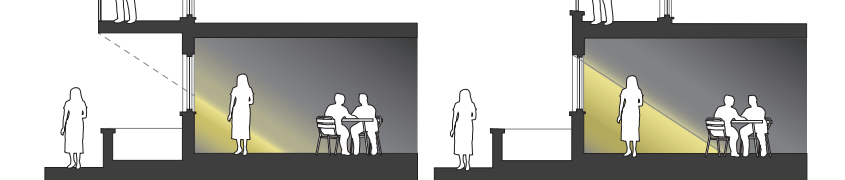

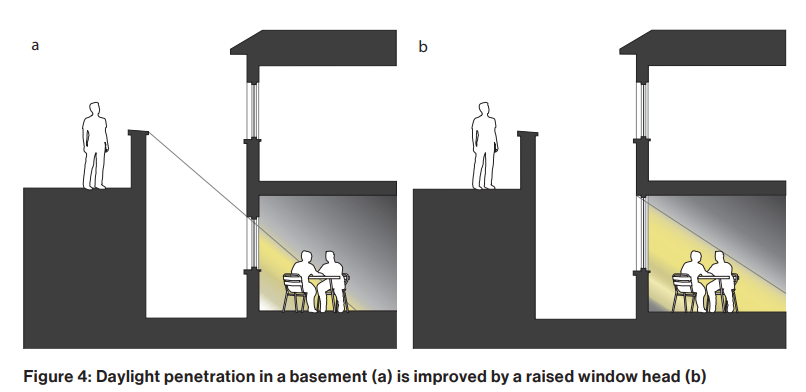

Window Sizes

As silly as it may sound, increase the size of the windows; the best way to do this is to raise the height of the window head, as this will improve both the amount of daylight entering through the window into the room, and also, a higher window head height will permit the light to enter deeper into the room. An illustration of the difference a higher window head height can give is included in Figure 4 of the BRE Guide:

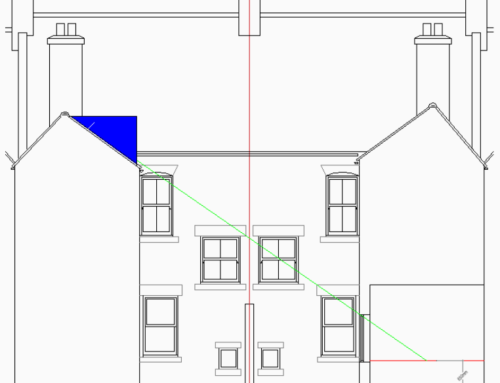

Window Locations

Again common sense dictates that to get good natural lighting, that windows should try to be positioned where most daylight is available. Positioning windows at the corner junctions of courtyard type buildings, or at the corners of L-Shaped blocks or wings, means that often these windows will be poorly lit, as the windows and rooms will be self-obstructed from the adjacent part of the building. Therefore, it makes sense to try and place the rooms that do not have a requirement for natural light in these areas; think staircases, bathrooms, storage space, etc.

Also, placement of windows in the centre location of walls can often allow the light to distribute both sides of the window, allowing better daylight distribution with the room. Placement of a window to one side of a rooms external wall, often only benefit one side of a room.

Room Depth

As well as considering the size and position of windows serving rooms, consideration should also be given the room shape and room depth. Deep rooms, and/or peculiarly shaped rooms, can make it impossible for the inner most parts of these rooms to be able to receive any direct sky light. Such rooms will be poorly day lit and more likely to fail the daylight tests in the BRE Guide. If you can incorporate windows on more than one wall – do it – multi aspect design will increase your chances of the design being better day lit.

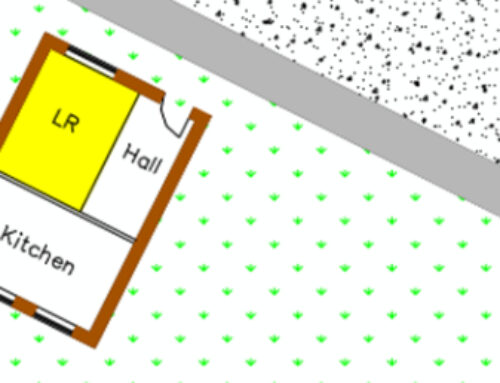

Room Uses

The BRE Guide does acknowledge that bedrooms require less natural light than other types of rooms, such as for example, living rooms and kitchens. Therefore, when designing the layout of a building it would make sense to place the living rooms and kitchens away from obstructions to light, whether these be obstructions caused by neighbouring properties, or, self-obstructions referred to above cause by ‘wings’ of a block.

Sometimes, neighbouring ground floor buildings may mean that some obstruction to your planned windows is unavoidable. In such situations, think about room placement. If all of your apartment is placed at ground floor level, and there are adjacent site restraints, you may find it difficult to provide natural light to the habitable rooms on this floor level. Hence, by designing apartments over two floors, habitable rooms can be placed on upper floors.

Consider trying to place non-habitable rooms that have no requirements for daylight or sunlight on this lower level, failing that, bedrooms, leaving the upper floors to rise above the neighbouring obstructions in question to serve rooms that have a higher requirement for natural light such as living rooms, dining rooms and kitchens. ‘Upside down’ housing often helps in such situations.

We have mentioned above that living rooms and kitchens require more natural light than other room types. The BRE Guide encourages designers to avoid non-daylit kitchens if possible (it does not exclude them). If a small internal kitchen is inevitable, try and link it directly to a living room or dining room that is well lit.

Reflectance of Materials

As well as direct sky light, the BRE calculations consider the surface reflectance values of external and internal materials/finishes. Hence, specifying materials and colours that have higher reflectance values will impact upon the results of the light calculations. There is a growing trend towards the specification of ‘green’ or ‘living’ walls – whilst they can look nice if maintained, and can have environmental benefits, the vegetation will absorb light and thus can have a detrimental impact on light results.

Balconies

Balconies are a common feature in many apartment buildings, providing sometimes the only outdoor amenity area that an occupier can enjoy. However, whilst they can provide a useful and desirable outside space to many, they can also be a nuisance to occupiers of apartments with rooms below. The overhang of the balcony will naturally create an obstruction to the view of the sky from a room placed below. This can be exacerbated if there are also large buildings opposite. Such obstructions, including the balcony above in the same development, can sometimes completely obliterate the view of the sky, and, thus adversely affect the light to the room in question. Indeed, sometimes, if it were not for the balcony overhang, the room may remain adequately lit, even with a large development opposite.

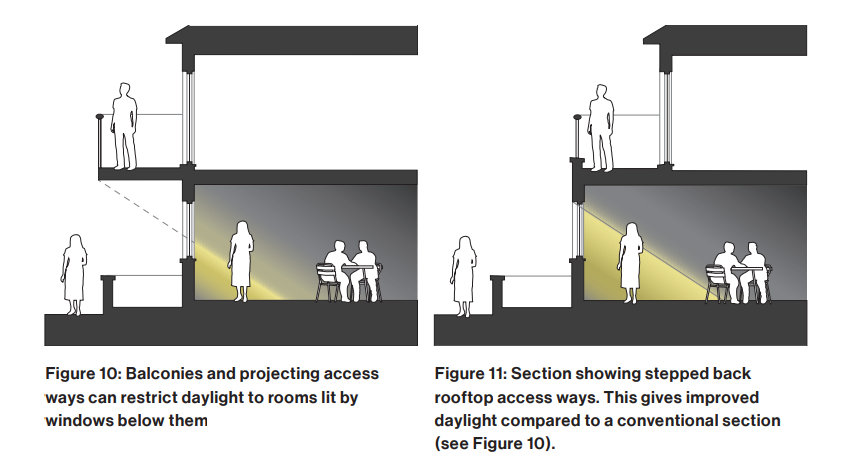

The BRE Guide highlights some methods for reducing the impact of balconies on rooms below as set out in section 2.1.18 of the Guide:

“Glazing in the balcony and making the resulting enclosed area part of the living room, gives a private internal space that can still receive daylight and sunlight. This is beneficial in obstructed ground floor rooms; otherwise, ground floor occupants are obstructed by the balcony above without having a balcony area of their own. Depending on the layout of the building, sometimes the façade can be stepped back to allow rooftop access or terraced gardens, without creating an overhang to the windows below (Figure 11)”

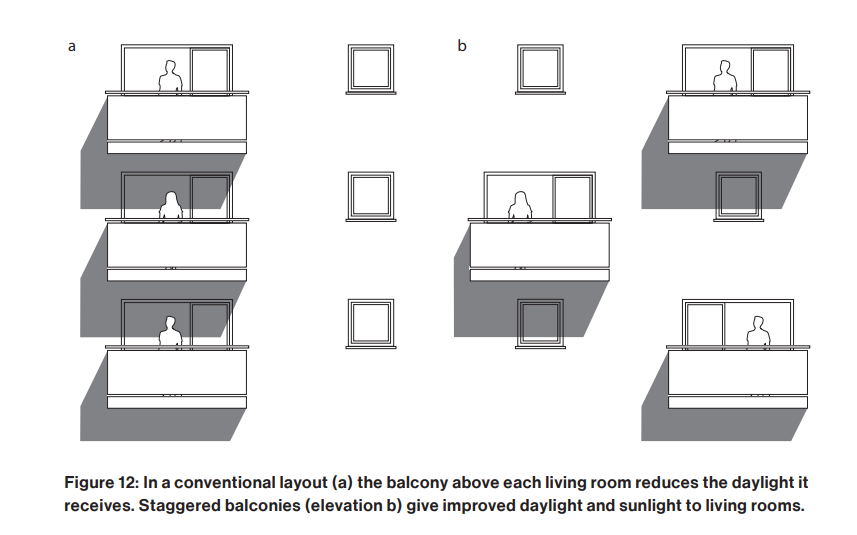

“Alternatively, balconies may be staggered so that a living room has its own balcony, but not one directly above it (Figures 12 and 13). Bathrooms or – in less obstructed situations – bedrooms could be sited underneath the balcony. Balconies may be arranged so that they are only partly above the windows to a room so that room can receive more daylight and sunlight from other, less obstructed windows. Having some unobstructed windows is particularly important if a neighbouring site is likely to be redeveloped in the future. A room that is heavily obstructed by its own design and reliant on daylight over low-rise neighbouring buildings may lose most of its light in the event of future changes to those buildings. One way to check this would be to carry out an additional calculation with notional future developments in place.”

SUNLIGHT

The above points consider daylight to rooms, although many of the design points can also contribute to how well a room may receive adequate levels of sunlight too, depending upon orientation.

The key points regarding the adequacy of sunlight are summarised in section 3.1.15, and in short are:

Try to have one habitable room in each flat (preferably a main living room) that faces within 90 degrees of due south

This is where the challenge lies for designers. In many developments, particularly those involving residential flats, it may not be possible to have every living room facing within 90° of south. This is a common problem with conversions of existing buildings, where there are natural existing building fabric constraints, often coupled with constraints from nearby existing properties, and, potentially also and often, the challenge is made worse due to the orientation of the property.

The BRE Guide lists some techniques to try and overcome such hurdles:

“- Having access ways and corridors on the north side, and living room windows on the south side.

– Where flats are grouped on both sides of a central corridor, having ancillary areas such as stairwells, lift cores, and bicycle storage on the north side of the building.

– Arranging the flats so that living rooms are placed at the end corners of the building and hence can be dual aspect. That way, living rooms on the north side of the building can also have an east or west facing window that can receive some sun.

– Alternatively, arranging the flats with a long north-south axis so that living room windows face east and west, and can all receive some sun.

Where groups of dwellings are planned, site layout design should aim to maximise the number of dwellings with a main living room that meets the above recommendations.”

Copies of the full document Site Layout Planning for Daylight and Sunlight – A Guide to Good practice, 3rd Edition” are available to purchase form the BRE Bookshop here https://www.brebookshop.com/details.jsp?id=328056

If you need a report to assess the levels of light your own proposed scheme will achieve, ask us for a ‘Within’ Daylight and Sunlight Assessment by contacting us at [email protected]

#daylight #sunlight #daylightandsunlightassessment #BR209 #BRE209 #BREGuide #SiteLayoutPlanning #architects #planningconsultants #propertydevelopment

Related Articles

Sunlight and New House Design: Avoid The Temptation to Use Standard Plans

Right to Light: Risks to Design and Build Construction Companies