Normal right of light threshold…

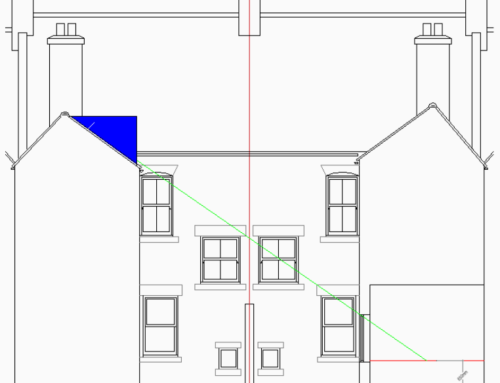

Past case law currently says that, in a standard situation, a room will be deemed to have suffered a legal right of light injury if it has some loss of adequately lit room area and, after this loss of light, less than about half of the room remains adequately lit by daylight.

The adequately lit aspect relates to which parts of a room (at the assessment height of 850mm above floor level) are able to see at least 0.2% of the dome of the sky. This is not a high threshold, amounting to only one lumen which is equivalent to a candle a foot away. This is currently the generally-accepted criteria for the assessment of legal rights of light matters as the amount of light sufficient for what has been referred to in legal cases as “the ordinary notions of mankind”. That is to say sufficient natural light for doing normally expected tasks, such as sitting at a table and reading a book for example.

For the majority of buildings, this is used by right of light practitioners and in legal cases as the accepted standard.

But what about rights to light for a greenhouse for example?

The test described as to what constitutes a legal injury is clearly  going to be reached for a greenhouse, with a glass roof; it is hard to imagine a situation where this could not be the case.

going to be reached for a greenhouse, with a glass roof; it is hard to imagine a situation where this could not be the case.

However, there is some case law to support there being an extraordinary right to light to certain buildings which have a non-standard need for light, such as a greenhouse. The most significant legal case is the 1978 Court of Appeal case of Allen and another v Greenwood and another.

In this case, it was argued for the Plaintiff that it should be the situation that: “the law will protect the dominant owner in the enjoyment of so much light as, according to the ordinary notions of mankind, he reasonably requires for all ordinary purposes for which the building is adapted”. It was further argued that the evidence was that the usage throughout the 20 years had been the normal and ordinary use as a greenhouse.

The argument for the Defendants was that the Plaintiff was only entitled to the ‘normal’ amount of light for ordinary usage of a building, thus that at least about half of the room should be able to see at least 0.2% of the sky. Also, there was argument for the Defendant that the claim was, in fact related to a loss of direct sunlight and not just daylight, and that there is no established right to sunlight.

The legal conclusion of this appeal was in favour of the Plaintiff in that it ruled that there was a right to more light for the greenhouse than the usual amount deemed to be appropriate according to the past case law. However, the legal opinions expressed in this matter did include comments that the usage of such a building must have been at the knowledge of the servient owner (the owner causing the blockage of light). The person blocking the light to a building with such an extraordinary need for light must have been aware of that use.

Any other building uses with an extraordinary right to light ?

From this, there must be the basis for a claim that the legal principle established in this case could be extended to say that other uses would be capable of obtaining (via Prescription) a right to more light than normal. This could include, for example, art galleries or studios used for precision work such as jewellery-making.

Additionally, other buildings might include buildings with stained glass windows which do not need more light internally but which do require extra light falling onto the external face of the glazing in order to achieve adequate internal daylighting due to the resistance to the passage of light of the stained glass.

Alternatively, there could be right to a higher standard of light via a Deed

The discussion above has been in relation to instances where it may be possible to obtain a right to more light than normal after 20 years by Prescription.

It must be borne in mind also that there can be instances where a higher standard of natural light may be the right of a neighbouring building as provided by an express or implied right of a deed. Here, we are talking not of a right via Prescription after 20 years but, instead, the existence of an easement created by an express provision or implied provision of a deed. For example, there may be such a right within the deeds of properties which state that nothing must be done which would result in any loss of light to a neighbour.

We intend to explore this further, separately, within another blog but this discussion would not be complete without some reference to this.

How we can help

Contact our team to discuss any right to light enquiries you may have, whether that be for your new extension or if your neighbour is planning a build that may cause a right to light injury for your home. Or whether if you have a more obscure structure such as a greenhouse that you would like to discuss.

Related Articles

8 Top Right To Light Misconceptions

Is There A Legal Right To Sunlight To Windows Or My Garden?

Right to Light & Dormer Windows