People often ask us whether there is a difference in natural light requirements for a property located in a suburban area versus one in a city centre setting.

This blog will explore your right to light in suburban vs city centre areas. Keep reading to find out more!

Firstly, What Does ‘Right to Light’ Mean?

In this context, ‘right to light’ is your building’s entitlement to unobstructed natural skylight (not sunlight) through the certain apertures, if rights have been acquired. Both commercial and residential properties may exercise a ‘right to light’, so offices and homes can benefit from the laws protecting a certain level of daylight. Legally, the Rights of Lights Act 1959, regulates the windows of domestic and commercial properties that have any rights, this was last updated in 2015.

Does My Property Have a Right to Light?

Most commonly, a property will acquire a legal right to light if the apertures have been present for 20 years. Rights to light can be obtained by other means, such as via a covenant, or, by implication, often following a sale of land from one party to another.

If the windows in your property are less than 20 years of age (and over 19 years and 1 day), then you will not have a legal right to light via Prescription, and in such cases, you would have to check your deeds, and past transfers of land to see if you have any rights by other means.

It is important to note that you needn’t have been the sole occupant of your property for twenty years, as the rights belong to the property.

If you’re uncertain whether you’re covered, speak to us prior to commissioning a right to light assessment.

How Does’ Right to Light’ Differ in Cities from Rural Areas?

Your entitlement as a property owner does not change depending on your location in terms of you being in the suburbs or in a city centre from a legal standpoint. However, your surroundings may impact the extent of issues you’re likely to face. Some environments present more threats to the daylight reaching your property than others, so it is worth noting the differences of properties in cities compared to rural areas.

Right to Light in Cities

As above, the amount of light required legally in a city centre property is the same as that in a property in a more suburban area. However, from a planning perspective, which considers daylight and sunlight, the tests considered as part of a planning application have different assessment criteria to those adopted for legal rights to light.

The key differences are that when assessing planning applications, the criteria for what constitutes adequate daylight and sunlight can be adjusted such that ‘alternative’ targets for levels of daylight and sunlight can be considered. In suburban areas, the targets tend to remain the ‘standard’ targets for daylight and sunlight set out by the Building Research Establishment in their publication “Site Layout Planning for Daylight and Sunlight – A Guide to Good Practice” (commonly referred to as BRE 209).

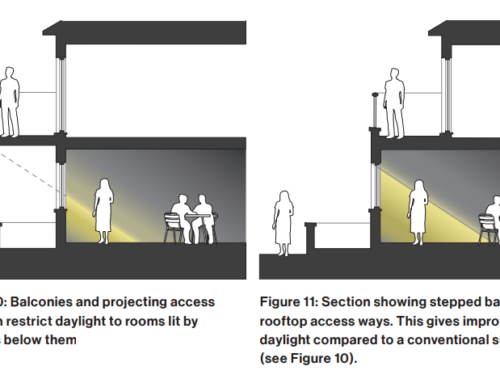

However, in cities the targets for daylight and sunlight from a planning perspective can often be justified as being lower. Given that city centre buildings are usually taller and closer together and are designed to match the surrounding streetscape, new developments need to be higher. As such, planning authorities will often accept lower targets for daylight and sunlight.

The downside of this is that by relaxing planning requirements for daylight and sunlight levels in cities, new developments are more likely to cause legal right to light injuries to neighbouring properties.

As such, it can be easier to cause a legal right to light injury in a city centre. Often neighbouring rooms can often already be poorly lit, meaning that the little light they already have can be deemed more precious. In circumstances where neighbours’ rooms are already inadequately lit, ANY further development that reduces sky view to such rooms, can create a legal injury.

Of course, many people expect less natural light in city dwellings, as they choose to live there for convenience, lifestyle, and proximity to work. As such, they’re often not as worried about the impact on their light. For this reason, many neighbours to developments in city centres simply accept such losses, without questioning them.

Whilst others who are more aware of rights to light or face significant right to light injury, will challenge city centre developments. Remedies to such parties can either be gaining an injunction to restrict the size of the proposed building, or agreement of financial compensation, which can (in certain circumstances) be quite sizable.

Right to Light in Suburban Areas

Living out of the city centre tends to appeal to families, and as such, people often value the natural lighting conditions in their home much more than perhaps those living in the city centre. As previously stated, the legal right to light thresholds are the same in suburban areas as they are in city centres.

However, in the suburbs, where peoples homes are affected, right to light matters often tend to be of more concern, and as such people are more likely to consider such matters and seek advice regarding their rights.

In the suburbs, most residential developments involve some form of extension or loft conversion, and of course, there remains the new build residential plots, often nowadays squeezed into large gardens of older, larger existing houses.

Such extensions can often impact on legal rights of light, even having secured planning permission.

How can there be a right to light problem if planning permission has been granted?

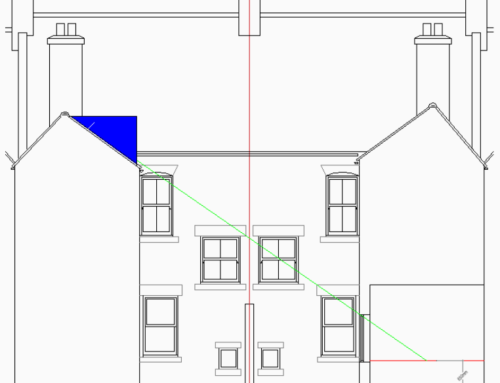

As previously mentioned, the tests for legal right of light matters are different to those considered at the planning application stage. Local Authorities do not consider easements which include legal rights to light. Local Authorities also do not consider the impact to light in non-habitable rooms such as stairs, landings, utility rooms, bathroom and toilets.

The result of this is that many residential developments sail through planning and gain approval, as the proposed developments often will only affect non-habitable rooms. Such rooms can and often will have a legal right to light and therefore, whilst not failing any tests from a planning perspective, can and do create legal right to light injuries.

The most common examples of this we come across day in day out are two storey side extensions (often over a garage), hip to gable roof alterations (to enable a loft conversion), and new build houses in a former garden, now built close to the gable wall of a neighbour.

What Should I Do If I have Right to Light Concerns?

You’re in the right place! Contact us for impartial advice, whether you are thinking of building, or if you are concerned that a development may affect your light.

Related Articles

Bungalows – Hidden Development Risks

Found The Perfect Development Plot? Beware of These Potential Light Constraints

Sunlight and New House Design: Avoid The Temptation to Use Standard Plans

Right to Light: Risks to Design and Build Construction Companies